Letter From Exile

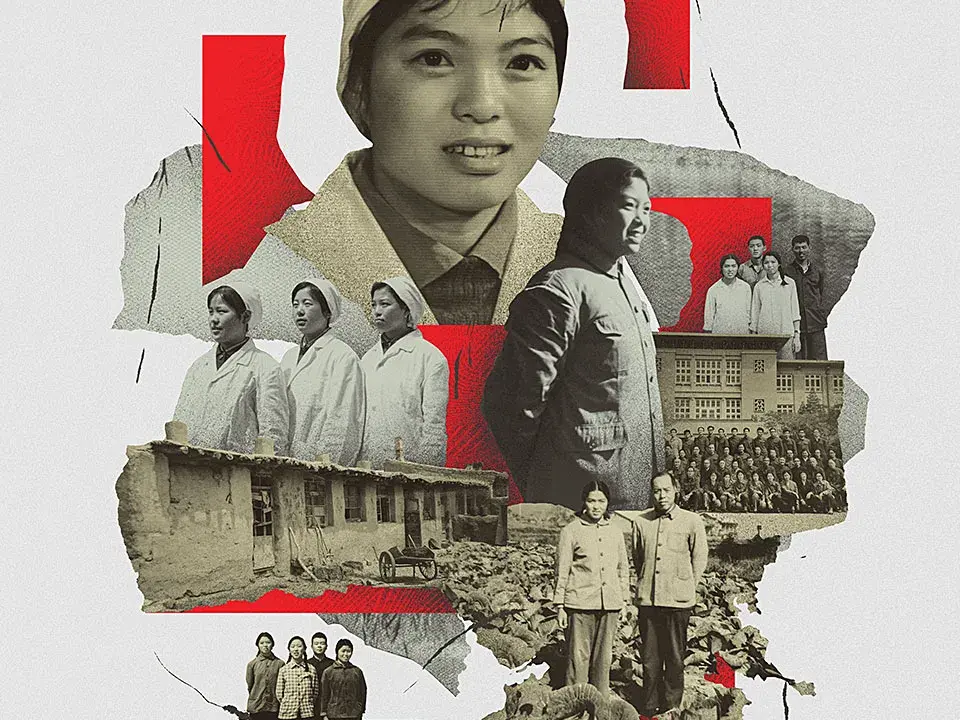

At 16, President Dr. Ching-Hua Wang’s life changed forever when she and other members of her family were rounded up, separated, and sent to work in remote factories and villages around China.

They were among an estimated 17 million middle school to college-aged students taken from their homes and families to be “reeducated” as manual laborers on farms, in camps, and in factories as part of the Communist Cultural Revolution. Many more professionals, government leaders, and artists suffered the same fate.

Her father, head of China’s World Affairs Press under the Department of State, was exiled to Jiangxi Province as a pig farmer. The oldest of her brothers, 13, was forced into hard labor for a construction company in Beijing until he broke his back, and Dr. Wang and her sister, 15, were sent to farming villages in Inner Mongolia.

Wang’s youngest brother, still in elementary school in 1966, was allowed to keep studying. Their mother was sent to work in a Beijing suburb and only allowed to visit the boy on weekends.

In Inner Mongolia, Wang lived in a subsistence farming village. Her home, a tiny, mudroom, had no running water, no insulation, and no electricity. “During winter, it was like Siberia. Minus 40 degrees Celsius. There were snowstorms and blizzards. Some people even froze to death,” Wang says.

Before her school and thousands like it were shut down by the government, Wang was a student of languages with an interest in diplomacy. In the village, she spent her days planting seeds, harvesting wheat, and raising sheep.

More than a year into her exile, Wang received a package from her father that, in all likelihood, changed her life path, leading her to college, medical school, and, eventually, to become a university president. Inside, was an Oxford English Dictionary. A gift, tailor made for his oldest daughter. It made her so happy, she remembers. “My father loved reading books. He had 1,500 books but they were taken away by the Red Guards. So, I don’t know where he got this dictionary because he was exiled himself, but he sent it to me anyhow,” Wang says. “That was my textbook.”

At night, she would sneak the OED out of its hiding place because books about the Western world and ancient history and culture were banned at the time. Using an old ink bottle filled with kerosene that she’d fashioned into a small lamp, she read the words over and over. “My nose would be black due to the smoke from the handmade lamp by morning,” Wang says.

She learned to pronounce the words by hiding under her blanket and listening to Voice of America on a transistor radio her parents gave her, also illegal at the time.

To this day, Wang holds the dictionary close to her heart. “It’s in a drawer in my office, after all these years,” she says. “Nowadays, I don’t need to use that dictionary, but I just want to keep it and pass it on. It has the pen markings that I had made during those Inner Mongolian years.”

Sorry, you’ve been blacklisted

After a few years in Inner Mongolia, some of the 13 middle schoolers that Wang arrived with from Beijing began to leave, assigned to jobs in other cities that would “benefit society," as the government put it.

Wang, who had finished just two years of middle school, when she was exiled, resisted. “I felt my learning was not done yet. I couldn’t imagine myself without further education.”

The first to leave was Nian-Sheng Huang, a young man from her old middle school. The two had grown fond of one another. Huang headed for a job in the capital of Inner Mongolia. When colleges finally re-opened, Wang, who by that time had been in Inner Mongolia for three years, applied to an English program but wasn’t admitted. The next year, she applied to a French program; same result. Still, she did not give up.

“I went to the headquarters of the commune and asked them how come I couldn’t get admitted by colleges twice in a row, and I asked why. The Communist Party official looked at my file. Everybody in China has a dossier so, they can check on you—all kinds of information, background you have, of your family, all the ancestors, all the relatives.”

She discovered that a distant relative had gone to Taiwan in 1949, fleeing the Communist takeover. Wang and her relatives were all blacklisted, deemed “politically not suitable to study foreign languages to become a diplomat.”

In her sixth year, Wang decided to apply to colleges once again. This time, the unexpected happened.

“The recruiter pulled me aside to his hotel room because he noticed my history of going once and twice and failed … He basically gave me a talk and said, ‘You need to change your major.’ And I told him, ‘I don’t really want to change my major. This is what I think I’m good at and I’d like to pursue that.’ And he said, ‘Look, how about studying medicine?’

Wang stood her ground.

The recruiter persisted.

“He said, ‘Studying Western medicine will require you to study foreign language. So, you can study foreign languages and you can study medicine as well. And this way you can go to college.”

“I realized he was trying to help me,” says Wang. “I agreed to change my choices and that’s how I got into medical school.”

The day Tiananmen fell

At Beijing Medical College, Wang “acted like a sponge. My brain was so open … after being so empty for so many years.” And though she had missed years of formal schooling, her study of the dictionary and a few other textbooks helped her to excel.

In medical school, Wang decided to become an ophthalmological surgeon and was able to do numerous surgical knots in record time.

Then an old finger injury from her days in Mongolia resurfaced. She ended up needing surgery, and it didn’t go well. The doctor had to amputate the tip of her index finger on her right hand.

Being a surgeon was out of the question, after that. It was a hard blow.

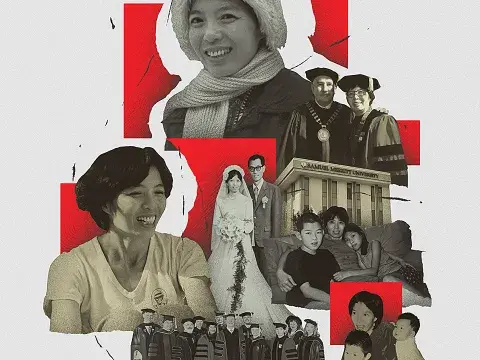

Still, Wang went on to graduate first in her 1978 class with a degree in medicine. She changed her focus to immunology and earned a master of science degree in 1981 from Beijing (Peking) University, Health Science Center, formerly known as Beijing Medical University.

While working on her thesis, she found that the leading immunologists were mostly based in the U.S. She decided to apply to U.S. doctoral programs and was admitted to them all, including Harvard. The first university to get back to her was Cornell, which also offered her a full scholarship. She accepted.

To obtain a passport, Wang needed permission from her university, where she was also teaching. The university president refused. “The country, the party, and the people educated you, and now you are leaving? It’s time for you to serve the country. Serve the people,” he said.

When all seemed lost, a colleague thought to ask Wang if she had a boyfriend. She did. By the end of May 1981, Wang had married Nian-Sheng Huang, the young man and schoolmate from Inner Mongolia.

She wrote a promissory note to the president: “I’m married, my husband is going to remain in the country, and I will go to get my PhD, and I will return to the country.” The president relented.

Within a few months, Wang was on a plane to Cornell University with only 10 dollars in her pocket. Not long after, her husband followed, first earning a master’s degree in American history from Tufts and then a doctorate in colonial American history from Cornell. The two made their home in Ithaca, raising two children. They had every intention of returning to China. But that changed in 1989, when the Chinese government declared martial law to squash student-led protests calling for democracy.

“When I finished my PhD, I was waiting for my husband to finish his PhD when the Tiananmen Square Massacre happened,” Wang says. “Many hundreds of students were killed during that massacre when they rolled out the tanks and they had guns blazing. And that’s when my husband and I, for our children’s sake, decided not to go back to China.”

Break the glass ceiling

In 1990, Wang became an assistant professor of biology at California State University, San Bernardino.

In 2001, she was selected from 2,300 candidates to be one of 13 founding faculty to establish California State University, Channel Islands. “Once I was recruited, literally, overnight, we had to learn how to start up a brand-new university from scratch,” Wang says.

While taking on more leadership roles, she continued to publish her research in some of the nation’s top immunology and biomedical journals, including Journal of Immunology, Clinical Immunology, Cellular Immunology, Cellular and Molecular Biology, and Clinical and Investigative Medicine. In 2008, she co-authored a chapter for the book, “Best Practices in Biotechnology Education.”

In 2012, Wang became dean of the School of Health and Natural Sciences at Dominican University of California, where she raised $9.3 million from private sources and corporations.

“That’s how I feel like I’m giving back to America,” Wang says. “Once I became a dean, it’s not about trying to climb the corporate ladder. It’s about serving others, helping others, helping more people to become successful. I had the opportunity to reach the American Dream; I want more people to achieve that dream.”

In January 2017, Wang was hired to serve as provost and vice president for academic affairs at California State University, Sacramento—a job she had no intention of leaving, even after Samuel Merritt University tried to recruit her as president.

“I was agonizing with this decision,” Wang says, explaining that she was impressed by everything she read and heard about SMU. So, she went to the president of Sac State and shared with him her dilemma. At first, she thought he would be upset. After all, she had arrived just two years earlier. But his words helped her know it was okay. “So, the president of Sac State, who hated to let me go, actually cried at my going away party. But he said, ‘If I were you, I would go.’”

He added that Wang would be helping to break the glass ceiling for other women, especially women of color. “He said, ‘You’re not doing it for yourself.’”

Keeping up with demand

On Nov. 26, 2018, Wang became the second president of SMU and the first native Chinese woman to serve as a university president in the U.S.

Recalling her time in the subsistence farm village in Inner Mongolia, Wang says, “That’s what made me decide to work to help low-income, first-generation students, and to help them move up. That’s my core mission.”

Finishing her second year as president, Wang says she’s proud of the “outstanding outcomes” of SMU graduates.

“As you know, we were ranked No. 1 in California in terms of our graduates’ salaries, especially nursing, which is our largest program,” she says. “It’s because of the faculty and staff who have worked here for so many years and being so devoted to the cause of higher education, health sciences education, that the students can become successful. I’m very impressed by that.”

Even so, Wang sees ways for the University to continue to advance.

“If you look at the Bay Area, we are short 58,000 nurses. Nationwide, we are short 200,000 nurses. If you put all the schools and programs together, we are not catching up with the demand. Therefore, there are a lot of opportunities for Samuel Merritt to grow,” says Wang.

To align that growth with the University’s long-term strategy, Wang has undertaken several new initiatives with the help of a newly assembled President’s Cabinet, including new vice presidents for academic affairs; university initiatives; strategy, innovation, and operations; student affairs, and advancement. At the top of the to-do list are implementing a newly developed Academic Master Plan, restructuring the division of Academic Affairs, developing new programs as well as expanding existing ones, and re-envisioning work and learning as well as physical space to support the University’s mission in a post-COVID-19 world. SMU also needs to spread the word about the University’s momentum and grow through new marketing initiatives.

“We have a lot to be proud of, while at the same time we have a lot to work on,” Wang says. “Our students, faculty, and staff are committed. With their passion, I see great things ahead for SMU. We should not let COVID delay our plan. We should forge ahead, putting in our level best to position the University for the future and make things happen.

“We are not stopping our efforts in terms of growth,” she explains. “We are still planning and working on growth. As we speak,nursing is developing three new programs. It’s really not limited to our four campuses. Because there is a tremendous need out there.”

For now, Wang’s top priority is “trying to preserve our jobs. The higher education industry, like many others, is facing a lot of pressure. While we are preparing for the worst scenario, we need to keep our highly productive and dedicated faculty and staff to deliver our mission and position the University for the future.”

Wang also hopes to do more to recruit women and people of color into senior leadership positions, noting that there are still too few faces of people who are not white and not men. “I need to help people and women with diverse backgrounds, who have the leadership quality to move forward,” Wang says.

Since the beginning of the year, the University has hired several new leaders from diverse backgrounds. College of Nursing Dean Lorna Kendrick is the only African American dean of a four-year nursing school in California, and one of only a few in the country. Chief of Staff to the President and Vice President for University Initiatives Emily Prieto-Tseregounis is the first Latina to hold this executive position. And Timothy Cranford was promoted to vice president for student affairs. He's the first African American to hold the position at SMU. In addition, the Board of Regents recently added its first Latino member, Neptaly Aguilera.

The University, Wang adds, is also striving to improve diversity among the ranks of faculty by working on a five-year diversity, equity and inclusion plan.

“We need to pay attention to diversity and inclusion. We are making history here,” she says.

“There are challenges, for sure,” Wang says. “But the University is very well positioned to not just survive but thrive, thanks to our well-qualified faculty, dedicated staff, and a diverse student body that we can build on, and an industry focus that’s needed more than ever, as the country’s population grows older and our healthcare needs increase. In fact, I’d say it's an exciting time to be president.”